' A State is civilised in proportion to the number of its members, who

have a lively sense of moral obligation... Where such a spirit does not

prevail, the most flourishing condition of commerce and manufactures will be

found an empty boat....'

(Thomas Beddowes, The History of Isaac

Jenkins, preface to the 5th edition, Bristol,

1793)

Most of the source books for this post are now available on the internet, and it is well worth reading some of them.

Most of the source books for this post are now available on the internet, and it is well worth reading some of them.

|

| Her Benny, A tale of Liverpool life. 1890 (Google eds. New York Public Library) |

In the 18th and the first half of the 19th centuries most children's

stories were written to serve a moral purpose by people who were working with

the poor. They saw it as very important to train children to be

charitable. There were very many stories written about the pleasures of

giving, and relieving the wants of the needy, rather than selfishly spending

pocket money on oneself. Children were encouraged both by stories and in

real life to visit the sick, to provide not only money but also to make and

give woolly scarves, baby clothes, plain sewn shirts and warm shawls to the

less well off. There was very little state help for the poor and charity was extremely important.

Since many of these stories were written by people involved in religious movements there is generally a lot about conversion and the power of prayer in them. Frequently the hero or heroine is exposed to, and resists, terrible temptation to steal or lie, cardinal sins for Victorian children. Benny, saved from sin by his sister Nelly, prays for forgiveness at her urging: 'If you plaise, Mr. God, I's very sorry I tried to steal but if you'll be a trump an' not split on a poor little chap, I'll be mighty 'bliged to yer. an' I promise 'e I won't do nowt o'the sort agin. (Silas Hocking, Her Benny, 1879)

Froggy, the crossing sweeper, when offered stolen money cries defiantly: "Take your two bob back again I say. I'd rather starve than steal...'('Brenda, Georgina Castle Smith, Froggy's Little Brother, 1875) The same innate honesty is apparent in Oliver Twist, an outstanding example of the Victorian belief that gentle birth somehow genetically transmitted such gentlemanly characteristics as honest, politeness and meekness combined with the ability to stand up fearlessly for the right. The appealing Oliver probably did as much as a whole series of Parliamentary Reports to arouse public concern for children in the parish workhouses, and for those neglected outcasts begging on the streets whom Fagin and people like him used and corrupted. The subtle irony of Dickens' description of Oliver's appearance before the Board of Guardians compresses into a few sentences the world of difference between observance of the spirit and the letter of the Acts for the training of pauper children:

'"Well! you have come here to be educated and taught a useful trade", said the red-faced gentleman in the high chair.

"So you'll begin to pick oakum to-morrow morning at six o'clock" added the surly one in the white waistcoat.' (Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, 1838)

Since many of these stories were written by people involved in religious movements there is generally a lot about conversion and the power of prayer in them. Frequently the hero or heroine is exposed to, and resists, terrible temptation to steal or lie, cardinal sins for Victorian children. Benny, saved from sin by his sister Nelly, prays for forgiveness at her urging: 'If you plaise, Mr. God, I's very sorry I tried to steal but if you'll be a trump an' not split on a poor little chap, I'll be mighty 'bliged to yer. an' I promise 'e I won't do nowt o'the sort agin. (Silas Hocking, Her Benny, 1879)

Froggy, the crossing sweeper, when offered stolen money cries defiantly: "Take your two bob back again I say. I'd rather starve than steal...'('Brenda, Georgina Castle Smith, Froggy's Little Brother, 1875) The same innate honesty is apparent in Oliver Twist, an outstanding example of the Victorian belief that gentle birth somehow genetically transmitted such gentlemanly characteristics as honest, politeness and meekness combined with the ability to stand up fearlessly for the right. The appealing Oliver probably did as much as a whole series of Parliamentary Reports to arouse public concern for children in the parish workhouses, and for those neglected outcasts begging on the streets whom Fagin and people like him used and corrupted. The subtle irony of Dickens' description of Oliver's appearance before the Board of Guardians compresses into a few sentences the world of difference between observance of the spirit and the letter of the Acts for the training of pauper children:

'"Well! you have come here to be educated and taught a useful trade", said the red-faced gentleman in the high chair.

"So you'll begin to pick oakum to-morrow morning at six o'clock" added the surly one in the white waistcoat.' (Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, 1838)

It is easy to deride these moral stories and to forget that when there was only very basic state provision for the poor the encouragement of private

charity was absolutely essential. Children's books, rather than adult

fiction, pioneered social realism in the portrayal of the conditions of the

poor long before the great adult social novels of the 1840s and 1850s.

The History of Isaac Jenkins, by Thomas Beddoes, physician and

close friend of the poet Coleridge, was published in 1793. It describes

the great harvest failure of that period and the effect on one poor family.

Here is part of the description of the sufferings of that winter:

'What

was to become of the poor, now their little store was all eaten and gone?...It

was bad already with them and a worse look-out...God be thanked; there are kind

charitable folks in the world, or else many an honest poor creature would have

perished for want that winter!...Notwithstanding there came great sickness over

all the country, and numbers were swept away by the spotted fever, especially

among the poor. It went worst with the little children, for they died,

generally one, sometimes two or more, where there were six or seven in a

family. And nothing was to be heard in the dark of the evening, but the church

bells tolling for funerals...' (Thomas Beddoes The History of Isaac

Jenkins, London, 1793)

Nonconformist Christian groups were particularly active producing moral

stories which described the conditions of the poor. Many of the writers

were actively involved in working with the poor, in Sunday schools and ragged

schools and various charities. The moral stories and religious tracts

were published by organisations such as the Society for the Promoting of

Christian Knowledge and the Religious Tract Society. It is hard to tell

how much influence they had on the children who read them but many

autobiographies mention famous titles such as the best-selling Jessica's

First Prayer by Hesba Stretton, 1866:

|

| Hesba Stretton (Sarah Smith) Jessica's First Prayer 1882 ed. (Archive.Org. University of Connecticut)Just one of many editions |

Children were taught to differentiate between the deserving and

undeserving poor, between those who kept their children clean and their houses

neat as a new pin, whatever the weather, and whether or not hot water was

easily available, and those sluts whose houses and children were filthy and

whose husbands, if they had them, spent their money at the ale-house or on gin.

The feminist campaigner Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women, also wrote the story of Caroline who has been allowed, as a moral lesson, to spend all her pocket money

on finery so that she has none left to help the poor family her guardian

confronts her with. Mrs. Mason, having looked about for a suitable object

of charity has found one: 'They ascended the dark stairs, scarcely able to bear

the bad smells that flew from every part of a small house, that contained in

each room a family, occupied in such an anxious manner to obtain the

necessaries of life, that its comfort never engaged their thoughts. The

precarious meal was snatched, and the stomach did not turn, though the cloth on

which it was laid was dyed in dirt. When tomorrow's bread is uncertain,

who thinks of cleanliness? Thus does despair increase the misery, and

consequent disease aggravates the horrors of poverty.'

(Mary Wollstonecraft, Original stories from

real life, 1788)

'There's a poor beggar going by,

I see her looking in,

She's just about as big as I,

Only so very thin.

She has no shoes upon her feet,

She is so very poor

And hardly anything to eat,

I pity her, I'm sure.

But I have got nice clothes, you know,

And meat, and bread, and fire,

And you, mamma, that love me so,

And all that I desire

.....

Here, little girl, come back again

And hold your ragged had,

For I will put a penny in,

So buy some bread with that.'

(Jane and Anne Taylor, Select rhymes for the

nursery, 1807)

After the revelations of the series of 19th century Parliamentary

Reports on labour conditions, the hardships of poverty were often exaggerated

by being described with unrelieved grimness for dramatic effect, while the

poor, as fictional characters, were often sentimentalised. Writers of

fiction both for children and adults found in the sufferings of the poor a

theme which moved their readers. The working children of the poor excited

particular concern partly because compassion of the weak and helpless was a

quality which Victorian society admired, partly because the Victorian middle

class was well on the way to creating a cult of cosy, sheltered childhood.

From Jane Eyre to Oliver Twist and Andersen's Little Match Girl, all

wrung the heart precisely because they were children enduring sufferings which

the reader no longer associated with a rather idealised idea of childhood.

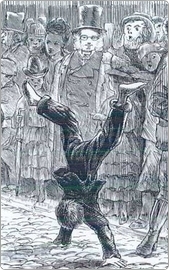

Charles Kingsley's famous book about the moral education of a young

chimney sweep boy, The Water-Babies was also inspired by

Parliamentary Reports into working conditions, in this case those of chimney

sweeps' boys, which had not improved much since the 1817 Report into their

conditions, mainly because no adequate system of inspection had been set up.

Lord Shaftsbury pressed for further reforms in the 1840s and Kingsley's

book helped to rouse public opinion. The Water-Babies is

a very unusual combination of fantastic fairy tale and social realism, and this

is probably why it became a children's classic when most moral stories have

been condemned as either too moralistic or too sentimental. ' "Oh

yes" said Grimes, "Of course it's me. Did I ask to be brought

here into the prison? Did ask to be set to sweep your foul chimneys?

Did I ask to stick fast in the very first chimney of all, because it

was so shamefully clogged up with soot? Did I ask to stay here - I

don't know how long - a hundred years, I do believe, and never get my pipe nor

my beer, nor nothing fit for a beast let alone a man."

"No", answered a solemn voice behind, "No more did Tom,

when you behaved to him in the very same way."' (Charles Kingsley The

Water-Babies, 1863)

|

| Mr. Grimes and Tom. Illustrator Anne Grahame Johnstone, c.1960? This children's classic ran to many editions.

Macdonald, himself from a poor background, included some pointed

criticism of the insensitivity of some do-gooders in At the Back of the

North Wind: 'I have known people who would have begun to fight the

devil in a very different way. They would have begun by scolding the

idiotic cab man; and next they would make his wife angry by saying it must be

her fault as well as his, and by leaving ill-bred though well-meant shabby

little books for them to read, which they were sure to hate the sight of; while

all the time they would not have put out a finger to touch the wailing baby.'

|

Few writers who wrote adult novels about the poor concerned themselves

with children, but there are a few exceptions. Dickens used

characters such at Tiny Tim in

A Christmas Carol and Little Nell in The Old Curiosity Shop to heighten pathos in his novels. Arthur Morrison in Child of the Jago wrote the entire

novel from the ;point of view of a child brought up in one of London's

'courts'; tenement blocks round a central enclosed square where, in some districts,

the police would only venture in twos.

|

| Arthur Morrison A Child of the Jago. (Illus: Londonfictions.com) |

Moore believed that his book helped to remedy this situation by

encouraging legislation making baby-farming illegal, and by helping also to

create sympathy for unmarried mothers.

(George Moore, Esther Waters, 1894)

The popular best seller Ministering Children, 1854, is not only about the satisfaction to be gained from helping the

poor, but about doing it in the right way, not just with money which might be

misused, but with visits to the sick, comforting broths, warm clothing and good

deeds. In the preface Maria Charlesworth explains her aim: 'May it

not be worthy of consideration, whether the most generally effective way to

ensure this moral benefit (of practising charity) on both sides, would not be

the early calling forth and training the sympathies of children by personal

intercourse with want and sorrow.' (Maria Charlesworth, Ministering Children, 1854)

|

| Ministering Children, 1867 ed. (University of California, Archive Bookmaker) |

'Parents and little children, you especially who are rich,

remember it is the Froggys and Bennys of London for whom your clergyman is

pleading when he asks you to send money and relief to the poor East End.' In Flora Thompson's Oxfordshire village where people were relatively

poor 'many tears were shed over Christie's Old Organ and Froggy's

Little Brother, and everyone wished they could have brought those poor

neglected slum children there and shared with them the best they had of

everything.' (Flora Thompson, Lark Rise to Candleford, 1945)

|

| Froggy's Little Brother by 'Brenda' 1875 (University of Roehampton) |

The pathos in most American stories about the poor, as in

Little Women, derives from the loss of a parent or facing straightened

circumstances rather than actual starvation, as in Susan Warner's best-seller Queechy, 1852 which was based on her own experiences. The popularity

of books like this and Little Women may have been partly due to the

uncertainties of life in America where fortunes were quickly made and as

quickly lost. The book was hugely popular in Britain with both adults and

children; in Susan Warner's biography it says there were ten thousand copies

sold at one railway station in England, but the publishers scouted the idea of sending the author a cent!'

The optomistic, resourceful orphan girl was America's unique

contribution to the genre in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Heroines such as Pollyanna, Anne of Green Gables,

Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, or Jo in Little Women faced up to a hard world and made it love them for their impetuous but

always good-hearted efforts to please and help others.

Mrs. Francis Hodgson Burnett, a British writer who emigrated to America

on her marriage successfully combined the two types of story into one of the

classics of its kind, A Little Princess, the story of a

little girl whose rich papa leaves her at a select boarding school

while he is on an expedition in search of further sources of wealth.

Letters stop coming and the bills remain unpaid. Vindictive Miss

Minchin makes Sara, once the prize pupil, into the school drudge. Throughout

all her trials she behaves with immense unselfishness and nobility. In

this enormously satisfying story the reader can not

only enjoy identifying with Sara through miseries that are, masochistically,

increased as a result of her immensely noble behaviour, but is rewarded not

merely by a happy ending but by even vaster riches than those of which

she was abruptly derived at the beginning of the book. Moreover she

magnanimously forgives Miss Minchin for making her the drudge of the school

when the bills stopped being paid.

|

| Illustration to an Edwardian edition (Fotobook.com) |

'...there came toddling up to them such a funny little girl! She had a great quantity of hair blowing about her chubby little cheeks, and looked as if she had not been washed or combed for ever so long. She wore a ragged bit of a cloak, and had only one shoe on.

"You little wretch, who let you in here?" asked Gruffanuff.

"Give me dat bun" said the little girl, "Me vely hungry."

"Hungry! What is that?" asked Princess Angelica, and gave the child the bun.

"Oh, Princess!" says Gruffanuff, "How good, how kind, how truly angelical you are !"...

"I didn't want it," said Angelica.

"But you are a darling little angel all the same" says the governess.

"Yes I know I am" said Angelica....' (William Makepeace Thackeray, The Rose and the Ring, 1855)

Edith Nesbit also gave a subtle twist to the Ministering Children theme:

'"Do you mean to say...that you and Alice went and begged for money for poor children and then kept it?"'

(Edith Nesbit, The New Treasure Seekers, 1904)